The concept of Precise Point Positioning (PPP) is based on standard, single-receiver, single-frequency point positioning using pseudorange measurements, but with the metre-level satellite broadcast orbit and clock information replaced with centimetre-level precise orbit and clock information, along with additional error modelling and dual-frequency pseudorange and carrier-phase measurement filtering (Bisnath et al. 2018).

In 1995, researchers at Natural Resources Canada were able to reduce GPS horizontal positioning error from tens of metres to the few- metre level with code measurements and precise orbits and clocks in the presence of Selective Availability (SA) (Héroux and Kouba 1995). Subsequently, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory introduced PPP as a method to greatly reduce GPS measurement processing time for large static networks (Zumberge et al. 1997). SA entailed intentional dithering of the satellite clocks and falsification of the navigation message (Leick 1995). Since SA was turned off in May 2000 and GPS satellite clock estimates could then be more readily interpolated. Hence, the PPP technique became scientifically and commercially popular for certain precise applications (Kouba and Héroux 2001).

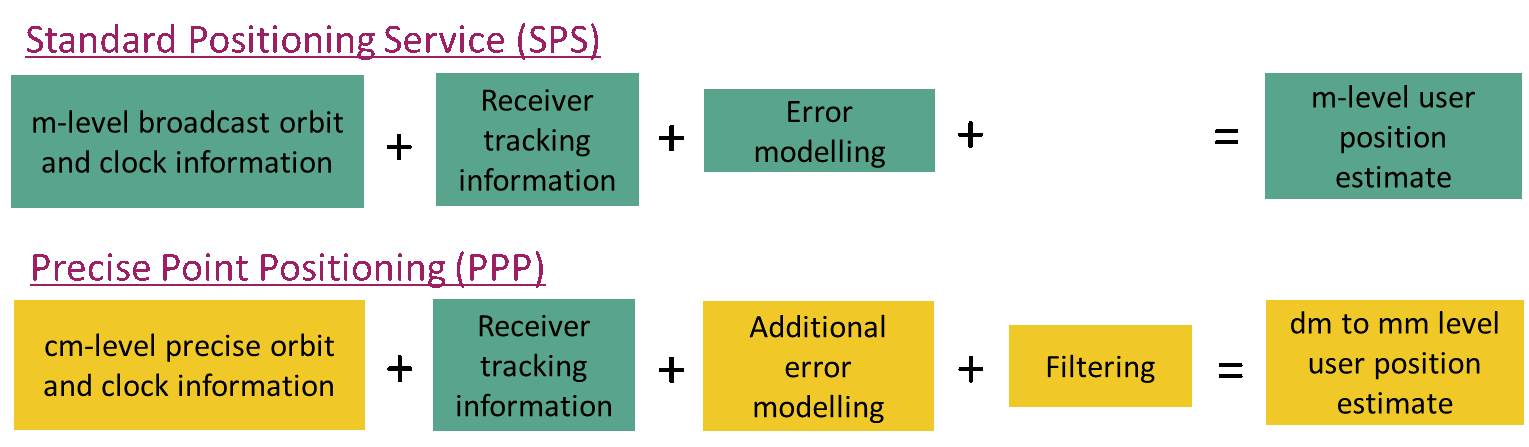

Unlike static relative positioning and RTK, conventional PPP did not make use of double-differencing, which is the mathematical differencing of simultaneous pseudorange and carrier-phase measurements from reference and remote receivers to greatly reduce or eliminate many error sources. Rather, conventional PPP applies precise satellite orbit and clock corrections estimated from a sparse global network of satellite tracking stations in a state-space version of a Hatch filter (in which the noisy, but unambiguous, code measurements are filtered with the precise, but ambiguous, phase measurements) (Bisnath et al. 2018). In conventional PPP, when attempting to combine satellite positions and clocks errors precisely to a few centimetres with ionospheric-free pseudorange and carrier-phase observations, it is important to account for some effects that may not have been considered in Standard Positioning Service (SPS). The GPS Standard Positioning Service (SPS) is a positioning and timing service provided by way of ranging signals broadcasted on the GPS L1 frequency. The L1 frequency, transmitted by all satellites, contains a coarse/acquisition (C/A) code ranging signal, with a navigation data message, that is available for peaceful civil, commercial, and scientific use (US DoD 2001). Figure 1.1 directly compares the approaches of SPS and PPP. In the SPS, metre-level real-time satellite orbit and clock information is supplied to the user by each GPS satellite. For single-frequency users, ionospheric refraction information is also required. For the troposphere a common mapping function for wet and dry troposphere is utilized (Collins 1999a) in contrast to PPP that considers different obliquity factors for the wet and dry components (Seepersad 2012). All of this information is combined with C/A-code pseudorange measurements to produce metre level user position estimates (Bisnath and Collins 2012). Where as in PPP, the same receiver tracking information as in SPP is utilized but cm-level precise orbit and clock information together with additional error modelling and filtering is utilized to enable dm to mm level user position estimation.

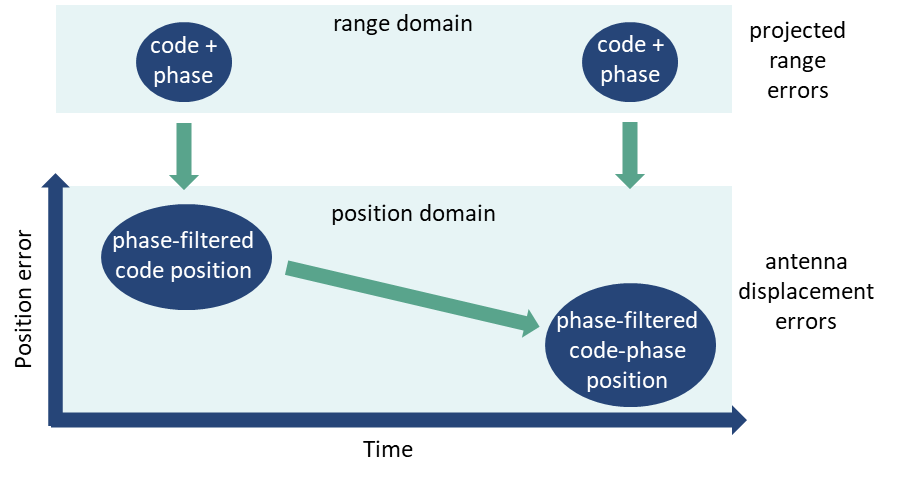

Also, defining the PPP error budget becomes more challenging as these error sources can be subdivided into errors projected onto the range and localized antenna displacements, illustrated in Figure 1.2. As the signal is transmitted from the satellite to the receiver, error sources affected in the range domain include satellite and receiver clock error, atmospheric, relativistic, multipath and noise and carrier-phase wind-up. Antenna displacement effects occur at the satellite and receiver and these include effects such as phase centre offset and variation, orbit and at the receiver, site displacement effects such as solid Earth tides and ocean loading. The measurements are continually added in time in the range domain, and errors are modelled and filtered in the position domain, resulting in reduced position error in time (Seepersad and Bisnath 2014a).

It is necessary when processing data with a PPP algorithm to mitigate all potential error sources in the system. As a result of the undifferenced nature of conventional PPP, all errors caused by the space segment, signal propagation and signal reception directly impact the positioning solution. Error mitigation can be carried out by modelling, estimating, eliminated through linear combinations of the measurements or filtering through time averaging. As previously mentioned, there are additional corrections which have to be applied to pseudorange and carrier-phase measurements such as phase wind-up, antenna phase centre offset and geophysical effects, in addition to other commonly known effects such as relativistic correction in order to have a complete observation model in PPP. Presented in Table 1.1 is a summary of all corrections accounted for and the applied within the mitigation strategy.

Table 1.1 Summary of error sources in PPP, mitigative strategy and residuals (Seepersad and Bisnath 2014a)

| Effect | Magnitude | Domain | Mitigation method | Residuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionosphere | 10s m | range | linear combination; estimation | few mm |

| Troposphere | few m | range | modelling; estimation | few mm |

| Relativistic | 10 m | range | modelling | mm |

| Satellite phase centre; variation | m - cm | position; range | modelling | mm |

| Code multipath; noise | 1 m | range | filtering | 10s cm - mm |

| Solid Earth tide | 20 cm | position | modelling | mm |

| Phase wind-up (iono-free) | 10 cm | range | modelling | mm |

| Ocean loading | 5 cm | position | modelling | mm |

| Satellite orbits; clocks | few cm | position; range | filtering | cm - mm |

| Phase multipath; noise | 1 cm | range | filtering | cm - mm |

| Receiver phase centre; variation | cm - mm | position; range | modelling | mm |

| Pole tide | few cm | position | modelling | mm |

PPP is considered a cost-effective technique as it enables sub-centimetre horizontal and few centimetre vertical positioning with a single receiver under ideal conditions with few hours of GNSS data (Seepersad 2012) in contrast to the methods such as relative GNSS, RTK and Network RTK that require more than one receiver. PPP can be used for the processing of static and kinematic data, both in real-time and post-processing. PPP’s application has been extended to the commercial sector, as well in areas such as agricultural industry for precision farming, marine applications (for sensor positioning in support of seafloor mapping and marine construction), airborne mapping and vehicle navigation (Bisnath and Gao 2009). In rural and remote areas where precise positioning and navigation is required, and no reference stations are available, PPP proves to be an asset. Based on PPP’s performance, it may be extended to other scientific applications such as ionospheric delay estimation, pseudorange multipath estimation, satellite pseudorange bias and satellite clock error estimation (Leandro 2009).

One of the major limitations of conventional PPP has been its relatively long initialization time as carrier-phase ambiguities converge to constant values and the solution reaches its optimal precision. PPP convergence depends on a number of factors such as the number and geometry of visible satellites, user environment and dynamics, observation quality and sampling rate (Bisnath and Gao, 2009). As these different factors interplay, the period of time required for the solution to reach a pre-defined precision level will vary (Seepersad 2012).

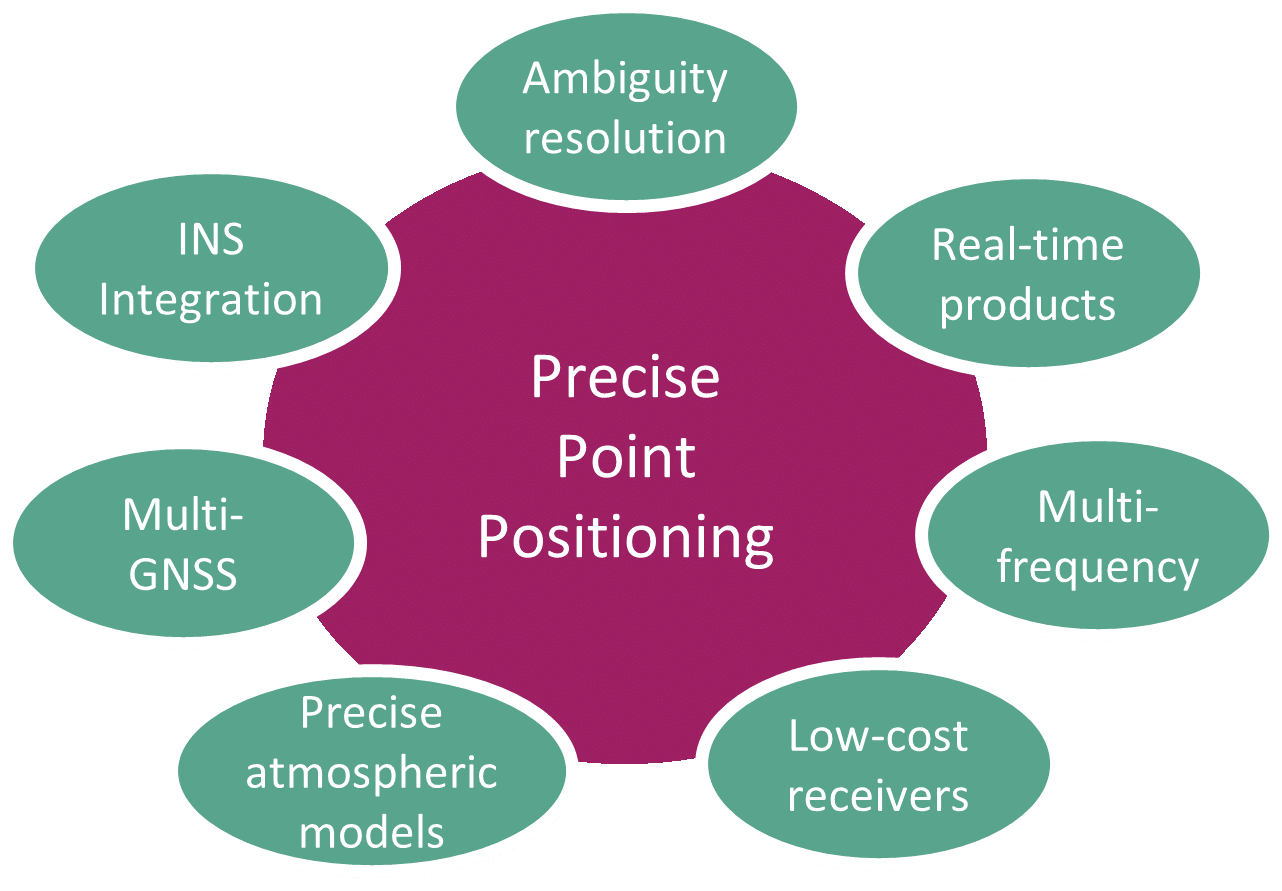

Within academia, industry and governments, there are key areas of focus within the PPP PPP GNSS measurement processing. These research areas include ambiguity resolution, integration of PPP and INS, precise atmospheric models, using multi-GNSS constellations and processing data collected with low-cost (single-frequency) receivers, illustrated in Figure 1.3. The improvements that these different methods to PPP can be categorized in terms of reduction of the initial and re-convergence period of PPP and improvement in solution accuracy.